James Purdy was a gay American author whose name I've occasionally seen mentioned in various magazine articles about gay American authors without ever familiarizing myself with any of his work. For some reason I always thought he was the author of Deliverance, which was actually penned by James Dickey, who was decidedly not gay.

Purdy, in addition to being a novelist, also wrote short stories and plays, although none of his work gained widespread acceptance during his lifetime. A member of Gertrude Abercrombie's underground salon during the 1930's, Purdy was highly influenced by the "New Negro Renaissance", then flourishing with the talents of Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughn and Dizzie Gillespie. While Purdy's work was championed by a number of literary notables (as well as the wealthy and influential Abercrombie, self-styled Queen of the Bohemian Artists), many critics found his tales of societal misfits to be outside the bounds of good taste, the graphic depictions of sex and violence too much for their refined palates. Being stigmatized as a "homosexual writer" ensured that Purdy would remain unknown to a large segment of American readers.

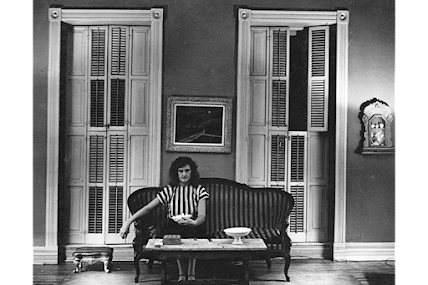

Even if his career was not on the same trajectory as some of his more celebrated contemporaries, Purdy led a fascinating life. In October, 2022, his biography, James Purdy: Life of a Contrarian Author (by Michael Snyder) was published by Oxford University Press. Until I read this biography there's not much more I can add about James Purdy that can't be found in his Wikipedia entry.

In the meantime, however, I do have a few things to say about Purdy's deliriously overheated Narrow Rooms, first published in 1978. The book spins a dark tale of the catastrophic repercussions of unrequited love and thwarted passions among a quartet of hot, bothered--and desperately unhinged--young men in a rural Appalachian mountain village. The first portion of the book focuses on the 20-ish Sidney De Lakes, a former football hero recently released from his prison cell into the loving arms of Vance, his slightly younger brother (the brothers are orphaned--a common trait shared by most characters in this book). Convicted of killing his male lover, Sidney is now a ruin of his former self, a man haunted by the past and stalked by spectres. As Sidney whiles away the time holed up in his bedroom, Vance, "prissy" and "Presbyterian", according to the author, is well-meaning and adoring but does not want to hear about Sidney's otherness, or of Sidney being "used" by fellow inmates in the state penitentiary.

In fact, while Sidney was "away", Vance was taken as a ward (more or less) by the village's elderly doctor who treats the boy as his son. Recognizing the likely end result of Sidney's self-imposed isolation, the doctor urges Vance to coax Sidney into the outside world. When, at last, Sidney does venture out, he encounters Roy Sturtevant--aka the Renderer--his former classmate and--seemingly--all-powerful nemesis who has an axe to grind with Sidney. Retreating back to the safety of his room, Sidney intends to stay there with his ghosts, guilt and self-loathing. However, the doctor soon arrives bearing news of a potential job opportunity for Sidney: caring for the invalid son of a wealthy local widow.

That Sidney will be hired seems to be a foregone conclusion but things go disastrously awry following a--briefly--promising start. Thus begins the book's second quarter, where we are introduced to Irene Vaisey and her son, Gareth. The actual source of Gareth's infirmity is nebulous: barely verbal, he appears incapable of moving or caring for himself in any way. Soon enough, Sidney has Gareth walking, talking and...um...well, you get the picture. In astonishingly short order, one thing leads to another. Irene, not entirely aware of the nature of Sidney's therapeutic miracles--but not exactly unaware, either--praises this newfound savior, but, for his part, Gareth is a snotty, ungrateful brat whose seemingly inexplicable recovery may signal something darker at work.

Joining Roy in this portion of the book is Brian McFee, the young man whose death landed Sidney in prison in the first place. Appearing via flashbacks and as an apparition, Brian may be the least psychotic member of the deadly quad at the dark heart of this fable, but he is no innocent, either. Death and destruction follow him as much as anyone else in this novel, they just catch up with him sooner.

There are times in Narrow Rooms where Purdy seems to be channeling Tennessee Williams. I'm not necessarily referring to Irene, although she wouldn't be out of place rubbing elbows with Violet Venable or Amanda Wingfield. The boys in this are all tortured Williams' divas, too. Really, could Sidney be any more like Blanche DuBois? Dreamy, spacey and beautiful, Sidney tells everyone he's in love with them, and, certainly, they all want to be loved by Sidney. Yet, paradoxically, none of these people really seems capable of love. Within the hothouse confines of Purdy's mountain town, these mad young beauties talk about love--a lot--but here, love equals obsession, obsession equals sex, and sex equals death. The only character who ever had a chance of escaping this toxic stew is dead before the book even begins.

And so the constant over-the-top hysterics of the main characters--Sidney, Roy, Gareth, Brian--ultimately becomes tiresome and self-defeating, never more so than when the book totally jumps the shark in its final quarter. This, of course, is when our four resident lost boys/drama queens are finally brought together for a grand guignol finale that feels positively operatic in its tragedy, bloodletting, and gonzo runaway train bravado. After all this, the actual ending feels anticlimactic. It seems to me that the story would have been better-served had Purdy wrapped things up in the preceding scene: with a bang, so to speak.

When I finished reading Narrow Rooms, I wondered why Purdy chose to portray all his queer (or non-heteronormative) characters as sad, tormented, violent and crazy. Had he experienced things of this sort when he was growing up in Ohio? Was it a rebuke of the Gay Liberation Movement which, by the time this book was written, had kicked down the closet door, initiating a previously verboten hedonism and transforming a subterranean, mistreated community into a garden of earthly delights? I wonder. I guess I'll have to read that biography!

With its heady population of misfits and miscreants, Narrow Rooms could easily be categorized as Southern Gothic. But, look deeper and you'll find elements of pure noir and classic pulp fiction: an easily manipulated victim of love who becomes the agent of his own destruction; the slimy, all-seeing master criminal/manipulator; a homme (rather than femme) fatale in the form of Gareth; a dead blonde; grave robbing, beatings, gunplay, rape, murder, and an overall atmosphere of claustrophobic dread.

And yet, there is something darkly, perversely humorous happening here, too, particularly in the gore-filled finale: to be sure, it's the blackest of comedies (if that's what Purdy intended) but it also frequently crosses the fine line between high melodrama and high camp.

Narrow Rooms is both Jacobean and Shakespearean, biblical and mythological, woozy and surreal. There is much sex between our four protagonists, none of it particularly erotic, and the plot, such as it is, seems more like a testosterone-fueled fever dream (or nightmare) than an actual novel. There are wonderfully descriptive passages interspersed with woefully awkward prose. Where was the editor when this thing was being published, anyway?

Still, I couldn't put it down. Narrow Rooms is, by no means, classic literature, but it is a distinctly American novel: there are echoes, however distant, of other, earlier authors (Faulkner, Hammett). While it is frequently problematic and transcends easy categorization, Narrow Rooms kept me engrossed (and sometimes appalled) for the few hours it took me to breeze through its 188 pages.

Comments

Post a Comment